This staccato passage from the “March to the Scaffold” appears shortly after the movement’s dark and ominous introduction. It is performed by all four bassoonists, and should be thought of in 2/2 with a tempo of approximately half note = 80.

Phrasing and Note Groupings

On the surface, this bassoon passage appears to be nothing more than a long line of accompanimental eighth notes—certainly nothing that would typically be considered “melodic” in nature. But although the strings continue on their melody from the previous phrase, at this point it is transformed into a light, pizzicato accompanimental line. The bassoons—despite the stepwise, continuo nature of their line—indeed have the melody.

Berlioz helps us with our phrasing decisions by separating some of the note groupings through his beaming, but only in certain instances such as the last three bars of Example 7.1. For most of the passage, though, Berlioz’s beaming does not indicate the phrase groupings.1

Example 7.1. Berlioz, Symphonie fantastique, Mvt. IV – mm. 56 to 59

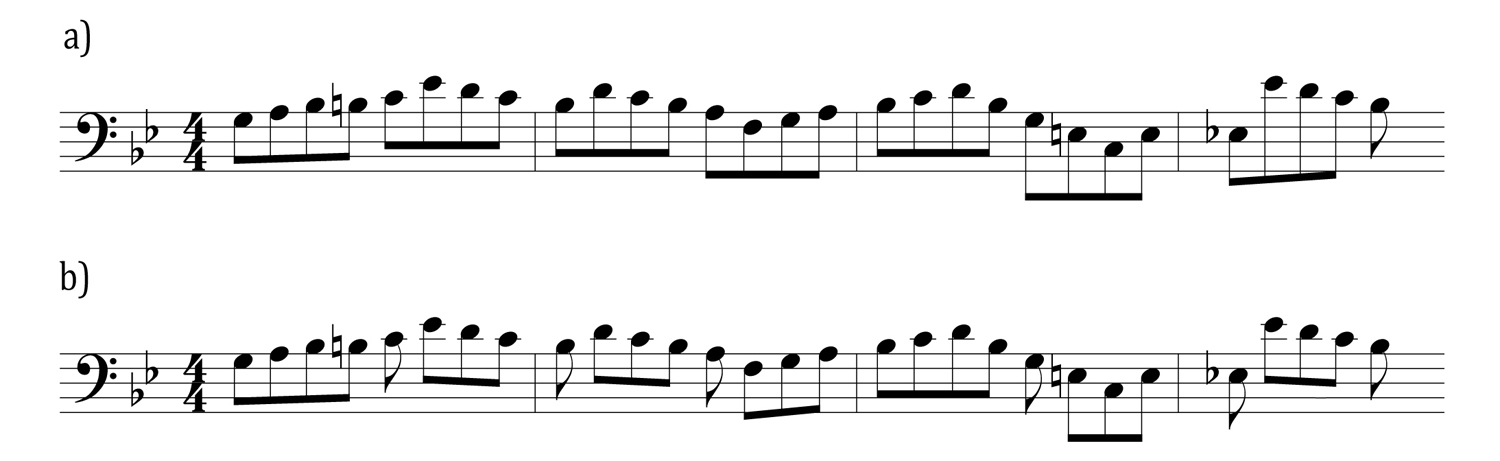

Example 7.2 provides an example of how re-beaming certain sections of this passage can help to clarify the note groupings: Example 7.2a shows the line as written by Berlioz, while Example 7.2b shows the same line with the beaming altered to separate the notes into their actual melodic groupings.

Example 7.2. Berlioz, Symphonie fantastique, Mvt. IV – mm. 51 to 54, original beaming and author’s alternate beaming

Choice of Articulation

The staccato notes in this passage should not end with the tongue; instead, each note should have a very slight taper at the end, creating a bouncy articulation that mimics the underlying strings pizzicatos. This type of staccato is closely related to Weisberg’s concept of “resonant endings.”2 In David McGill’s discussion on staccato notes, he writes:

With string instruments, the bow keeps moving between the notes and the string itself continues to vibrate after the bow ceases to make contact with it.3 No such reverberation happens with a wind staccato. In order to bring the staccato off successfully in wind-playing—to create and maintain a musical line—one must carefully judge how much a puff of air to give each note. The player must also build in a bit of resonance by controlling how much of a “tail” each note should have.4

This type of staccato requires a slight amount of jaw movement, since the embouchure must quickly increase its pressure to counterbalance the drop in pitch that occurs during the taper of sound.5 As you can hear in Roger Norrington’s recording with the London Classical Players, this style of tapered staccato was actually very natural for the bassoon of Berlioz’s time. One important note: when moving to the two extreme ranges of the excerpt (in mm. 54 to 55 and 59 to 60) I find that eliminating this motion and focusing on a tongue-stopped staccato will ensure that the notes speak without delay.

1 See the pedagogy section for “Dream of a Witch’s Sabbath” for more on Berlioz’s note beaming and groupings.

2 For more information on resonant endings and the other types of articulations discussed here, see Articulation.

3 The string also continues to vibrate in this manner during pizzicato playing.

4 McGill, 191.

5 For very fast tonguing passages (such as the excerpt from the fifth movement) this jaw movement is to be avoided.